Things I Once Knew is a survey exhibition of the work of Tasmanian artist and furniture maker Patrick Hall, representing the development of his artistic practice from the mid-1980s to the present.

Exhibition runs from 20 March – 30 August 2015

Have a read of the speech by our home grown hero, Richard Flanagan.

Pat Hall and I share several things: a bad education at what was—at that time—hailed on local talkback radio as the worst school in Tasmania, Geilston Bay High School; a love of literature, and two front teeth. The teeth were Pat’s. I use the past tense advisedly.

It was thirty-four years ago, a group of us were decamping to Bruny Island for a week, and Pat was coming with us.

He came to the share house I then lived in—a slum of such sickly decrepitude and dampnessthat anaemic yellow grass grew in the lounge room—at about midday the day before we were to depart. In the kitchen we had assembled our supplies for the five days we would be away: five trays of out of date Four ‘n’ Twenty party pies plus a bag of potatoes someone’s mother had left in act of maternal—if misplaced—optimism. Above these humble offerings there rose to the ceiling a monumental ziggurat composed of twenty-seven Coolabah wine casks.

On Pat’s arrival we decided it wise to test the wine for corkage, beginning with the Fruity Lexia. Several hours passed pleasantly, deconstructing the upper levels of the ziggurat, at which point we decided to drive to the Uni Bar.

Halfway there my car ran out of petrol and the seven people in it, including Pat, then helped push it into the old Barrack St service station. It was, in the way of bad beginnings, a dark and stormy night. And just as we made it to the bowsers Pat—perhaps if I am to be honest, a little lexiaed— slipped on the rain covered bitumen, and went flying into a metal rack of oil bottles. There was a terrible noise of scattering and smashing glass as he went down.

For a terrible moment nothing moved. We stared horrified at the fallen form of a future Tasmanian living treasure, possibly already dead, spreadeagled over a catastrophe of Ampol bottles and broken glass, a broken raft of a man adrift a large and growing slick of black oil.

And then, finally, Pat returned to this earth, groaned, moaned, moved and staggered to his feet. His face was not unlike Tony Abbott’s after eating an onion—a strange pursed look, uncertain about something but not sure what. It was also covered with sump oil. There may have been vomit involved. I can’t precisely recall. I do know a collective decision was made to take Pat home, which was at that time in South Hobart, shared with his beloved twin sister, Belinda.

First, however it was felt best, particularly in view of Belinda’s sensibilities, that Pat be cleaned up. With garage rags we scrubbed his face until the oil was mostly gone and only an almost explicable grime remained. Coats were swapped, water drunk, we arrived at Belinda’s, and rang the front door bell.

I do remember we were holding Pat up in the manner a broomstick does a scarecrow, our hands scruffing the back of his jumper. The door opened, Belinda stepped out, Pat smiled and then—Belinda screamed. Given the length we had gone to clean Pat up this was unexpected. It was only when Pat turned, waved us goodbye, and smiled that we realised what neither he nor we had known until that moment: his two front teeth were missing.

Since that sorry revelation I must confess I’ve been happy that Pat didn’t die that night in what is now the Hobart BMW Autohaus. For one thing we wouldn’t have this remarkable body of work. For another he’s a dear friend. And though I should be standing here solely out of guilt and shame, I am also standing here with an enormous sense of pride—not because I think Pat Hall is a major Tasmanian artist, but because I think he is a major artist, full stop.

There was a period of over a decade when it was very rare to see Pat Hall work anywhere in Tasmania as—like our abalone—it was all being snapped up by overseas markets—in Pat’s case by rich American collectors. This show reminds us all of just what an extraordinary achievement Pat’s body of work is.

Walking through this exhibition with Pat earlier this week I realised that there arose in Tasmania in the 1980s a remarkable generation of artists, craftspeople, poets, architects, and writers. As successive governments sought to drag the island backwards into a nightmare of division and destruction, these artists were taking it forward, reinventing the island as an invitation to dream a new world.

Highly influential on that generation were Pat Hall’s two great mentors who turned the Tasmanian Art School’s Design in Wood course into a mecca for so many. One was Kevin Perkins—whose work includes the prime ministers office in the new parliament house—the other, John Smith. John, like Kev, was a leading furniture maker designer.

In the third room of the exhibition are two lovely sister pieces, one for Kev, showing his beloved 1958 Merc, the other for John, showing an E-Type Jag, the car that inspired John to become a designer.

John was married to Pat’s elder sister, Penny, and he was to Pat at once his guiding inspiration, a dear friend, and a father figure. John Smith passed away two weeks ago. No one would have been prouder of Pat, of this exhibition and all it represents tonight than John.

Pat began as a furniture maker who believed furniture could have personality and his early pieces retained the faux reality of a cabinet or wardrobe or some such, while all the time really existing as laughing questions, as novels dressed up as chest of drawers and display cabinets.

Pat Hall very early on developed a highly distinctive style—ever charming as well as beautiful, witty as well as warm, full of visual puns, and often very funny. Teetering piles of furniture disguised as art throw a shadow that is Michelangelo’s David. The wonderful cupboard of art tomes called “Tall stories from the Art world” has titles as variously ridiculous as Cubism Goes Full Circle, or Futurism—A Retrospective.

Pat Hall’s work is often about a severe order being disrupted by the human comedy. Wherever classification reigns, the chaotic madness at the heart of human existence breaks through again and again in Pat’s work, playing out as whimsical tragedies.

Looking at these mini- wunderkammers —some of the best examples of which have been kindly lent by David Walsh from the MONA collection—I can see why David Walsh feels such a strong connection with Pat’s work and has been such an important patron. For in one sense MONA is a Pat Hall piece writ large—a series of intricate and elaborately conceived jokes asking large and serious questions.

A carapace of charm and graceful irony hides an often hard politics which gets stronger over passing years—from his earliest work here—the anti-Reagan Saloon drinks cabinet to the swaying aluminium skyscrapers of Towerland —his comment on the rise of the super rich in the early 1990s— to the more recent “Desert Island Disc’ in which a vinyl 78 of South Pacific spirals out into a long line that sits at the height the Pacific Ocean is expected to rise over the next century because of global warming.

The increasing intricacy of Pat’s creations through the late 1990s showed the influence of the celebrated jeweller and Pat’s soul mate, Di Allison. Pat’s works became labyrinthine creations—cupboards of short stories that added up to a novel you could store your underwear in—made with ever increasing finesse and craft.

Look, for example, at the exquisite detail of the miniature aluminium quilt on ‘Not Dark Yet’ being waved by a robot, or admire the extraordinary detail of the cabinet called ‘Bounty’. At the base of that work is a small three-inch high scrimshaw mural which shows a long ocean. Look closely and you’ll see two hundred years of a certain history begin with sailing ships and end with an airliner slamming into two towers.

Or there is the mesmerising mandala-like Historical Record #1 — a globe of the bones of the dead around which colonisers’ ships sail. Constructed with a watchmaker’s perversity, some of the bones look a little dirty—as if charred and buried for along time. Look closer though and ghostly faces begin to form on the smallest of knuckles—Marlon Brando’s mad Fletcher Christian, Picasso’s unerring eye; the drummer boy of Gunter Grasses Tin Drum.

There is a terrible yearning for something forever lost and unobtainable in Pat’s work. Perhaps it’s anything but coincidence that he collects the humblest materials of the dead—78 records, 35 ml slide mounts, bones and pins and shards of pottery—and with them creates ghosts lighting our way through the strange beauty of this world to our own dusty deaths, restoring meaning to things that long ago lost them.

The humility of the objects mirrors the humility of the art and the man, and there is in all this some fundamental assertion of the dignity of everyday lives too easily dismissed as everyday.

Walking around this exhibition you may notice a slow transition from the humorous and whimsical in Pat’s earlier works, to the darker and more personal, from story telling wardrobes and cupboards and dressers leavened with laughter to the pieces that run the risk of being called art. In this Pat is not blameless, but it’s hard to say whether Pat caught up with art, or rather, as is more likely, art caught up with Pat.

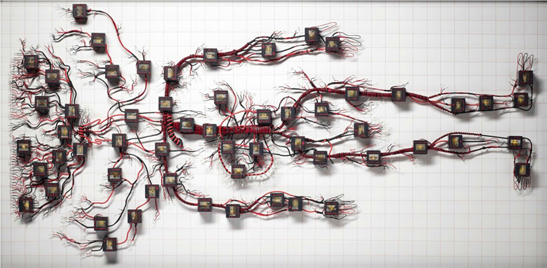

The most recent piece in this exhibition is the astonishing Depth of Field—800 slide mounts behind which 2400 images of lace, wire, sticks, fishing line, mesh and fraying electrical wire play out behind it in shadow play, a spectral, noirish shadow drama made more mysterious by the way in which overlaid over the whole is an image of a human nervous system.

The stories—once such a staple of Pat’s work— are mostly gone, and what remains now is a fundamental essence.

Perhaps, says Pat as we look at it, its about how nothing can be captured. We really don’t know anything at all.

Pat Hall’s is finally a poetic vision of life. Style is the man, and like Pat, the humility of these works belies a richness of thought and intricacy of soul.

One of my most precious belongings is a work Pat Hall once very generously made for me as a gift. It takes the form of an elaborate fish tank. Encased inside is a rolling pewter sea across which a small ship steams, bravely heading into uncertain waters.

Beneath the ship, along the length of the glass case, he has etched the following words: “When all the time we want to move the stars to pity”

That line is the final part of one of my favourite passages in all litearture, from Flaubert’s Madame Bovary: “Why is it,” writes Flaubert, “that none of us can ever express the exact measure of all our thoughts and needs and sorrows, and all human speech is like a cracked kettle upon which we tap crude rhythms for bears to dance to, when all the time we long to move the stars to pity.”

I know Pat would claim to have done no more than make a few cracked kettles, but whenever I look at that brave little boat on my bookshelf, cleaving to its compass, I think of Pat, and his life, and I try not to think about his lost front teeth.

And wandering this exhibition, looking at a life of his work, I came to think that Pat’s ship had finally made to port here tonight, while above us, in all their wonder, the stars are moved to pity.

TMAG is to be congratuated for starting to engage with the considerable achievements of contemporary Tasmanian art with retrospectives such as this. In reminding us of the richness of our greatest and most beautiful dreams, they honour not only Pat Hall, but give hope to us us all.

Thank you.